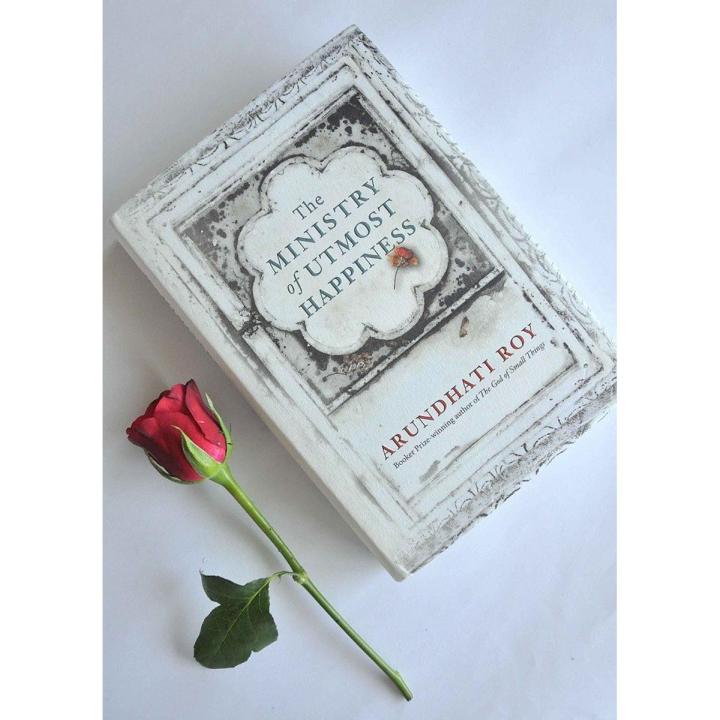

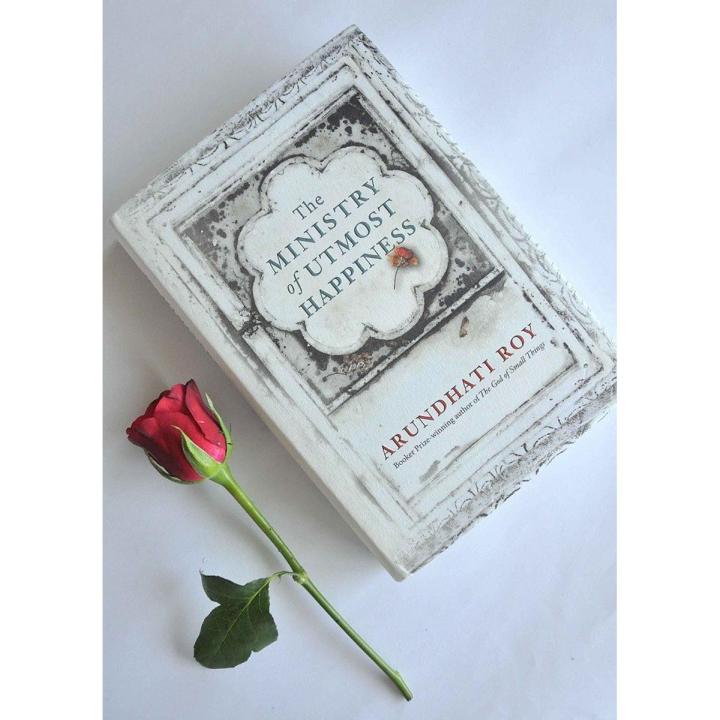

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy | A book summary for youth

To live with dignity in the face of adversity is the real triumph of the human spirit.

Normality is a myth invented by those who are lucky enough not to be different.

In the midst of war and ruin, there are always tiny islands of happiness.

Imagine a world where the most unlikely people – those rejected, forgotten, or broken by society – come together to build their own place of love, survival, and belonging. That’s the heart of Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. It’s a journey through India’s backstreets, graveyards, and conflict zones, where characters like Anjum, a hijra (transgender woman), and Tilo, a woman drawn into love and resistance, search for meaning in a fractured world.

The novel begins with Anjum, born as Aftab in Old Delhi. From childhood, Aftab knows he is different. His body doesn’t fit the world’s idea of “male” or “female.” His father prays he’ll grow out of it; his mother weeps in secret. Eventually, Aftab leaves home and joins the hijra community, where he becomes Anjum.

Anjum lives between beauty and pain. She dresses in bright saris, sings, laughs loudly – but inside, she carries the wound of rejection. She dreams of love, marriage, children, but society sees her only as an outcast. Yet Anjum refuses to vanish. Over the years, she builds herself a home in a graveyard, turning it into a strange but magical place – a guesthouse for strays, misfits, animals, and those who have nowhere else to go. The graveyard, instead of being a symbol of death, becomes her kingdom of survival.

While we follow Anjum, the story also shifts to Tilo, a woman with a completely different life. Tilo is educated, sharp, and independent, but never quite fits into society’s mold either. She has three male friends – Naga, Biplab, and Musa. They all circle around her like planets, but it is Musa, the Kashmiri man, who claims her heart.

Picture: Wikipedia

Musa’s story pulls us into Kashmir, the blood-soaked valley where beauty and violence exist side by side. Through Tilo’s eyes, we see the unspeakable: young men taken away in the night, bodies disappearing, mothers waiting endlessly for sons who never return. Musa becomes a militant, fighting against the Indian state, while Tilo risks her own safety to stay close to him. Their love is tender but also tragic, shaped by war.

Roy does not keep the novel neat. She lets it scatter, like broken glass reflecting different lights. Alongside Anjum and Tilo, we meet:

- Saddam Hussain, a Dalit man who witnesses his father’s brutal lynching by upper-caste men. Traumatized, he renames himself after the Iraqi leader Saddam Hussain – because he watched a video of Saddam’s execution and felt that this foreign man’s dignity in death gave him courage. Saddam wanders, survives by odd jobs, and eventually joins Anjum’s graveyard community.

- Animals and orphans, including rescued dogs, abandoned babies, and nameless wanderers – each finding shelter in Anjum’s world.

- Biplab Dasgupta, a government officer, who secretly narrates parts of the story. He is loyal to the state but also conflicted, torn between propaganda and the reality he witnesses.

The two main threads – Anjum’s personal journey and Tilo-Musa’s political love story – slowly converge. The bridge between them is a baby. Tilo finds an abandoned child during one of her journeys, and this child eventually comes into Anjum’s care. The graveyard guesthouse becomes the “Ministry of Utmost Happiness” – a symbolic place where people with broken pasts create a family of their own.

By the end, the Ministry is home to Anjum, Saddam Hussain, Tilo, the baby, and a mix of people who don’t belong anywhere else. They are all scarred – by gender rejection, caste violence, political war, or personal loss – but together they stitch a fragile kind of happiness.

Themes Weaved into the Story

- Identity and Belonging: Anjum shows how society tries to erase those who don’t fit its rules, but she builds her own space of dignity.

- Love in Conflict: Tilo and Musa’s love is tender yet impossible, proving that even in war, humans long for intimacy.

- Politics and Oppression: From Gujarat riots to Kashmir’s violence, Roy brings real history into fiction, forcing us to see the cost of nationalism, religion, and war.

- Resistance and Survival: Whether it’s a hijra in Delhi or a mother in Kashmir, the book shows how people resist erasure by creating meaning in small acts.

Why This Matters for Youth in Bangladesh

For a young Bangladeshi reader, this book may feel far away – India, Kashmir, different politics. But at its heart, it asks questions we face too:

- How do we treat those who are “different”?

- How do we talk about people silenced by power?

- Can love survive in the middle of chaos?

Common mistakes our youth make:

- Ignoring or mocking marginalized groups, like hijras or ethnic minorities, instead of seeing them as equal humans.

- Believing that politics is “boring” or “not our problem,” even though political violence and injustice affect every ordinary life.

- Thinking happiness means escaping from problems, instead of finding dignity within them.

The novel teaches us that happiness isn’t always shiny or perfect. Sometimes it grows in the middle of graveyards – among the broken, the rejected, the exiled.

Example: In Dhaka, transgender women still struggle to be accepted. A youth-led initiative that trains them in crafts, or gives them roles in businesses, creates not just jobs but dignity. That’s building a “ministry of happiness” right here.

Another example: When students in Rangamati organized cultural festivals for indigenous communities, they gave visibility and respect to voices often ignored. That’s another form of resistance and love.

Final Note of mine

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is not an easy read – it’s messy, painful, and full of unanswered questions. But maybe that’s the point. Life itself is messy. And yet, like Anjum, like Tilo, like Musa – people keep going. They find laughter in graveyards, love in war zones, and hope in abandoned children.

For Bangladeshi youth, the message is: we don’t need to fix the whole world to make it better. Sometimes, creating one small safe space – where outsiders feel seen, where dignity is restored – is enough.

🌿 Because the true “ministry of happiness” is not built by governments. It’s built by people – like us – who choose compassion over indifference.

About the Writer

Arundhati Roy is not just a novelist – she is also an activist, a fighter with words. Her first book, The God of Small Things, won the Booker Prize in 1997. But she didn’t stop at fiction – she used her voice to speak against war, injustice, and inequality. After almost 20 years, she returned with The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Unlike a simple story, this book is like a patchwork quilt – woven with politics, history, love, and the voices of people on the margins of Indian society. If you want to purchase this book yourself, Bangla version: দ্য মিনিস্ট্রি অফ আটমোস্ট হ্যাপিনেস and English version: The Ministry of Utmost Happiness