Climate, Poverty, and People: My Reflection on Bill Gates’ Message for COP30

In his recent newsletters and Gates Note, Bill Gates writes with a tone that feels both urgent and grounded – a…

Shahriar K Fahim

Shahriar K Fahim

Hi! I’m a Speech Therapist turned Social Entrepreneur, Development Worker, and Disability Activist.

Shahriar K Fahim

Shahriar K Fahim

Hi! I’m a Speech Therapist turned Social Entrepreneur, Development Worker, and Disability Activist.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how the stories leaders tell can push people to vote, protest, or even change their whole view of the world. We call these “narratives” – basically, they’re like tales with a beginning, middle, and end that make complicated ideas feel simple and real. In politics, these stories aren’t just for fun; they’re tools that shape what we believe and the choices we make. Think about the recent student protests here in Bangladesh – those weren’t random; they grew from stories about unfair systems and a fight for justice. But why do these stories work so well?

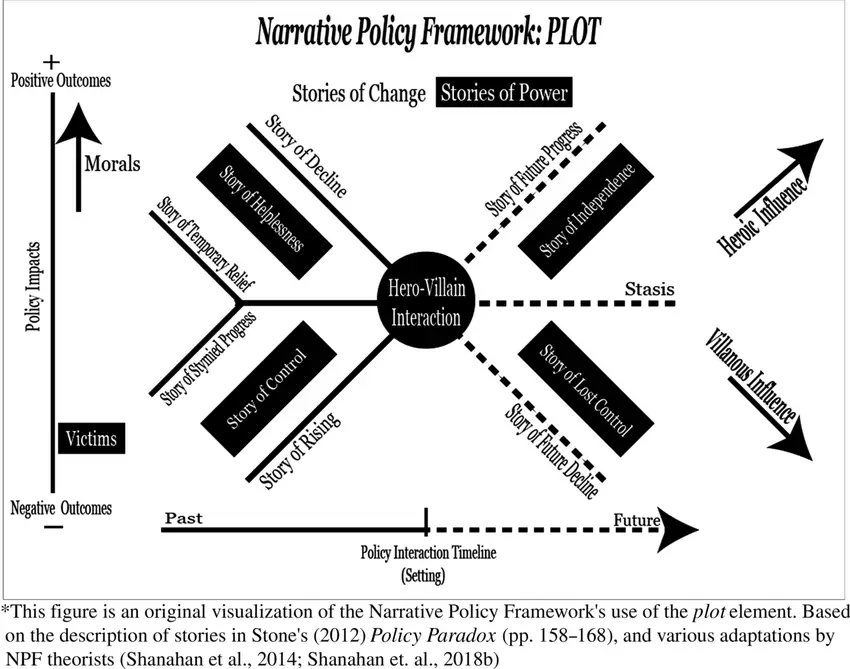

First off, let’s break down what makes a political story tick. At its core, a narrative has a clear setup: it paints a picture of a problem, introduces good guys (heroes who fix things), bad guys (villains causing the mess), and victims (people getting hurt). There’s always a moral or lesson at the end, like “we need change now!” This structure helps because our brains love stories – they’re easier to remember than dry facts. For instance, in Bangladesh, during the 2024 quota protests, the story was simple: students as heroes fighting a rigged job system (the villain being old rules favoring certain groups), with everyday youth as victims of inequality. This setup spread like wildfire on Facebook and TikTok, getting thousands to hit the streets. But it’s not just about the plot; these stories tap into feelings like anger or hope, making us feel part of something bigger. Researchers call this “resonance“ – when a story matches what we already feel deep down, it sticks and pushes us to act, like joining a rally or sharing a post.

Some Theories about this

Theories on how stories shape politics include Narrative Paradigm (Walter Fisher), which says humans understand the world through stories, requiring “probability” and “fidelity” for believability—like the 1971 Bangladesh war story fostering patriotism. Framing Theory (Erving Goffman) explains how politicians highlight certain issues to shape perception, while Agenda-Setting Theory shows how media focuses attention on specific topics. The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) suggests people process information either deeply or quickly, with politicians targeting the latter through social media. Spiral of Silence explains why unpopular opinions are silenced, and Cultivation Theory argues that constant media exposure makes the world seem more threatening, influencing political views.

For further reading on these theories, check out:

Cultivation Theory: Cultivation Theory

Narrative Paradigm: Walter Fisher’s Narrative Paradigm

Framing Theory: Framing Theory by Erving Goffman

Agenda-Setting: Agenda-Setting Theory

ELM: Elaboration Likelihood Model

Spiral of Silence: Spiral of Silence

The Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) is a way to understand how leaders use stories to push for change. They often create a story with a villain (someone to blame) and a hero (usually themselves) who promises to fix the problem.

For example, in India, when Prime Minister Modi launched the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) campaign, he told a story where dirty streets and poor sanitation were the result of past neglect. He made himself the leader who would clean up the country, calling on citizens to join in. It worked because people connected with the message and wanted change. Similarly, in Bangladesh, leaders often tell stories during elections where they blame “corrupt elites” or “enemies of the country” and present themselves as the ones who will save the nation. These stories shape how people see problems – and who they trust to fix them.

What is corrupt elites?

A corrupt elite refers to a small group of powerful individuals in society—who may hold political, economic, or social status—that use their position and influence for personal gain, often to the detriment of the broader public interest. This form of corruption, sometimes called elite capture, involves the siphoning of public resources through practices like preferential contracts or misuse of funds, rather than outright criminal acts. To know more about this, click here.

The Dark Side: How Narratives Can Be Weaponized

But beyond political shift, the most dangerous aspect is how easily narratives can be weaponized. They move beyond persuasion into the realm of psychological manipulation. A narrative framing political opponents not just as rivals but as ‘enemies of the state’ or ‘anti-nationals’ is a tool for manufacturing consent – making the public accept undemocratic measures as necessary for survival. This is where the hero-villain tale turns toxic, dehumanizing the ‘other’ and making violence seem justifiable.

Here, we’ve seen this with terms used to describe opposition groups, which are then amplified by organized troll armies on Facebook and Youtube. These paid commentators don’t just debate; they swarm, bully, and create an echo chamber so loud that moderate voices are silenced, pushing the overall political discourse to more extreme ends.

Now, how do these narratives actually sway our decisions? It’s all about the mind games they play. Stories trigger emotions faster than facts – fear of losing jobs might make you vote for a tough leader, or hope for equality could spark a protest.

Psychologists say we have biases, like “confirmation bias,” where we grab onto stories that match our beliefs and ignore the rest. In Bangladesh, think of how social media amplified tales of police brutality during protests; videos and posts made people angry, turning online outrage into real marches.

Internationally, it’s the same: the article I read talks about how big old stories in the West – like conservatives pushing freedom and growth, or social-democrats fighting for equality – are fading. Why? Globalization and climate change make promises of endless progress feel fake. In the US, Trump’s “Make America Great Again” story paints a lost golden past, blaming immigrants or elites, which hooked voters feeling left behind.

This exhaustion of old tales leads to wild swings: more people skip voting, parties splinter, and extremes rise, like far-right groups in Europe gaining ground by spinning fear of outsiders. In Bangladesh, we’ve seen this too – narratives around floods or economic woes blame “foreign interference,” pulling people toward nationalist choices.

In places like India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan (the sub-continent), social media is like a super-fast story machine, but often twisted with fakes. Fake pages pretend to be real news, posting cut-up videos or quotes taken out of context – like snipping a leader’s speech to make them say something bad they didn’t mean. They add emotional music, dramatic sounds, or sad tunes to hit your feelings hard, making you angry or scared without thinking. This builds false narratives, like claiming “minorities are attacking” during unrest, fueling hate.

For example, during Bangladesh’s 2024 protests, Indian fake reels spread clips saying Hindus were targeted, but fact-checkers showed many were old or edited videos from elsewhere, with music amping up fear to stir anti-Bangladesh feelings. In Pakistan, spy-linked accounts push anti-India fakes, like altered army videos with tense music, to build a “enemy next door” story. In India, during elections, reels cut quotes from opponents, add heroic or villain music, and go viral, swaying votes on communal issues.

Deepfakes (AI-faked videos) make it worse, like fake speeches spreading division. This hides truth, creates echo chambers (where you only see agreeing stories), and can lead to real violence, as seen in riots sparked by misinformation.

Studies show this thrives because algorithms push emotional stuff for more likes, and low fact-checking lets it spread. In our region, with big youth on TikTok/Reels, it’s powerful – one fake clip can change minds faster than facts.

As a youth, I’d say our first duty is to become narrative detectives. Start by spotting the heroes and villains in every news segment and political speech- ask, ‘Who benefits from me believing this?’ and crucially, ‘Who is being demonized and why?’

This isn’t about becoming cynical; it’s about becoming engaged. In Bangladesh, we have the power to harness this same storytelling force for good. Imagine building a new, powerful narrative around our collective resilience. A story that doesn’t rely on old villains but on shared goals.

Globally, as the old narratives of endless growth crumble, we have a chance to write a new one. It must be a story of sustainable futures, justice, and hope that includes everyone. It starts with us, the youth, refusing to be passive consumers of tales and instead becoming the authors of a better plot. What’s a narrative you will question today? Share below!

Thank for giving me your time while reading this. Getting anyone’s time is the most precious thing for me. To read my other blogs like Building Social Business by Yunus | A book summary for youth, Phobia to Nervous moment? Is it normal?, and The Shondha River Stole My Childhood: Why I’m Fighting Climate Anxiety, you can click here.